Energy News Beat

Total Employment to be substantially revised higher early 2025 when the BLS incorporates these up-revisions into its household survey employment data.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

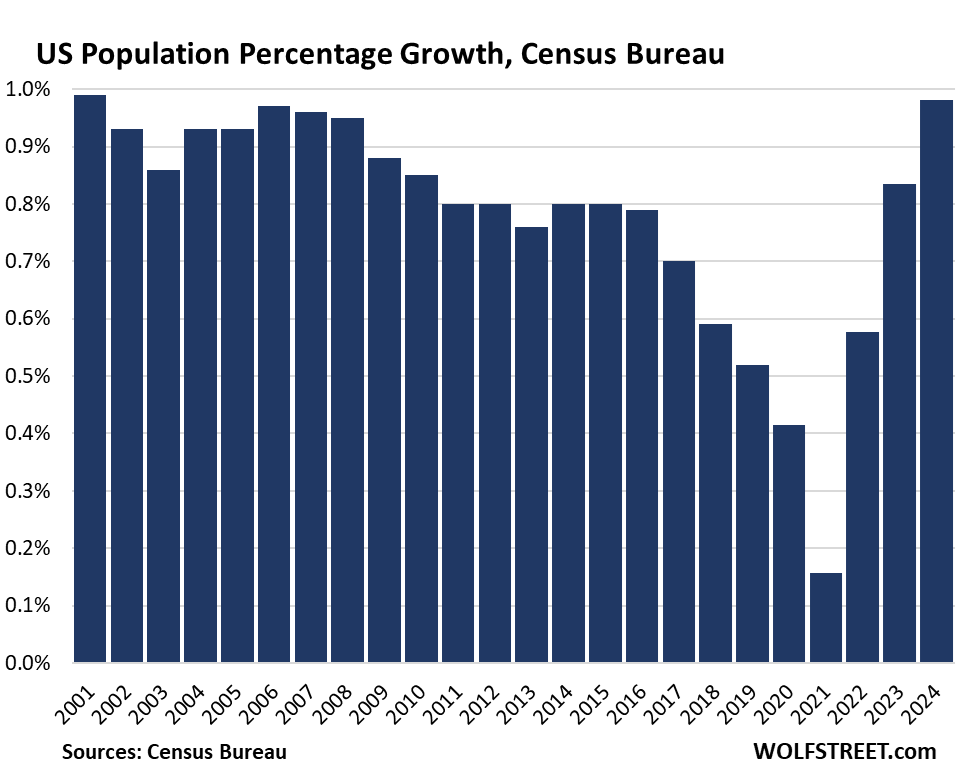

The Census Bureau released its updated population estimates with data through July 2024 today, which corrected its vastly underestimated figure of immigrants for the past few years.

The prior Census Bureau data had so inadequately measured the tsunami of immigrants in 2021 through 2024 that it left policy makers, such as the Fed, in the dark about the supply of labor, employment, etc. To provide some insights, the Congressional Budget Office released its own estimates of population growth earlier this year, by incorporating data from Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Today’s data by the Census Bureau confirms that it was truly a tsunami of immigrants that washed over the land. And now it’s official.

The US population surged by 8 million people in the three years from July 2021 through July 2024, to 340.1 million, according to the updated estimates from the Census Bureau today.

The 3.3 million net increase over the 12 months through July 2024 was the largest in decades. And the biggest portion of increases came from net-immigration (those that came in minus those that left or were removed):

- 2022: +1.92 million, incl. 1.69 million net immigration

- 2023: +2.80 million, incl. 2.29 million net immigration

- 2024: +3.31 million, incl. 2.79 million net immigration

In terms of the 2.79 million net immigration in the 12 months through July 2024, the Census Bureau said in its note about the improved methodology that this was “significantly higher than our previous estimates, in large part because we’ve improved our methodology to better capture the recent fluctuations in net international migration,” by among other things using “newly available administrative data [including from the Department of State Bureau of Consular Affairs and Refugee Processing Center; and from Homeland Security] to adjust the usually survey-based estimates of foreign-born immigration.”

“Improved integration of federal data sources on immigration has enhanced our estimates methodology,” The Census Bureau said.

In percentage terms, the population increased by nearly 1% over the 12 months through July 2024, the biggest percentage increase since 2001.

Over the three years through July 2024, the population increased by 2.4% (by 8.0 million people):

Coming Up-Revisions of Total Employment & Labor Force.

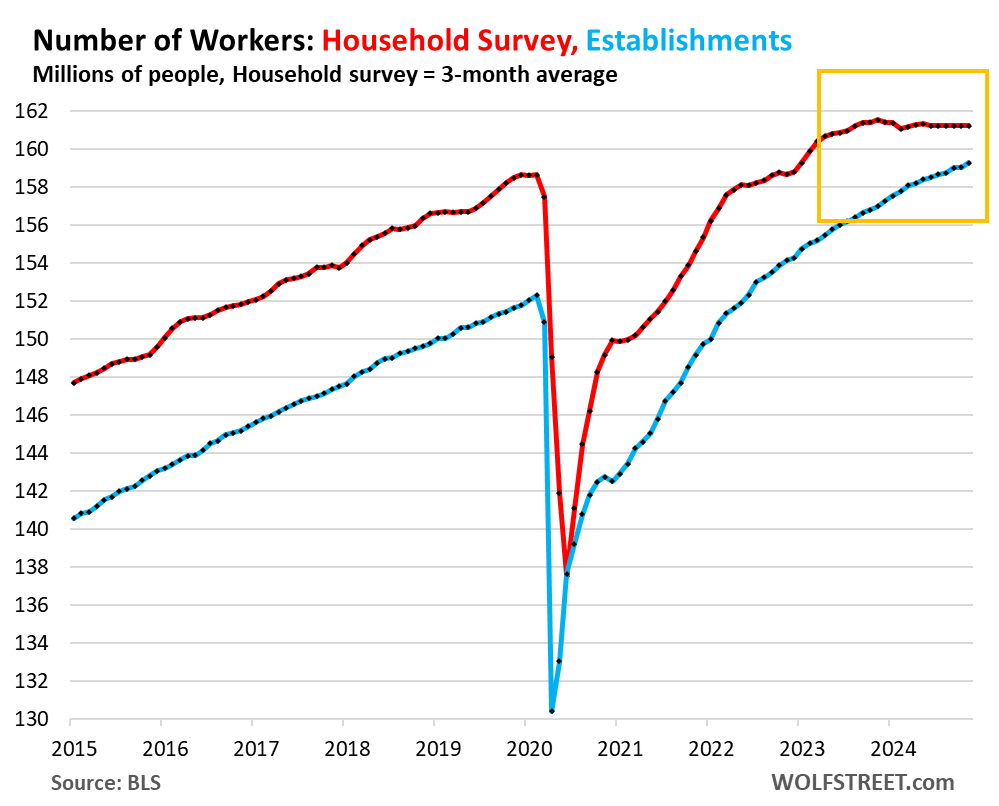

Early next year, the Bureau of Labor Statistics will incorporate these new population data into its employment-related data obtained from the household survey and substantially revise up its figures for labor force, total employment, and unemployment, and the metrics derived from those.

The household survey data – labor force, employment, unemployment, etc. – has been in the fog for two years due to this large underestimation of the working new arrivals and new arrivals still looking for work.

For the BLS employment data, legal status of the workers is irrelevant. It’s not even part of the data.

The newly arrived immigrants who either already have a job or are looking for a job count in the labor force, regardless of legal status. If they’re working, they count as workers, regardless of legal status. Those that have not found a job yet, but are looking for a job, show up as unemployed regardless of legal status.

So we expect large up-revisions of overall employment, the labor force, unemployment, and related metrics.

But the up-revisions might not move the unemployment rate much since they would largely cancel out in the calculation of the unemployment rate: up-revised number of unemployed divided by up-revised labor force.

The up-revision should re-establish the historic difference between total employment, which is based on the household survey and population data (red line in the chart below) and nonfarm payroll jobs, based on data from establishments (blue).

That long-established and normally fairly stable difference between total employment and nonfarm payrolls is mostly caused by certain self-employed workers and farm workers not being included in nonfarm payrolls, but being included in total employment.

By not adequately accounting for the newly arrived immigrant workers, total employment (red) stopped growing and even declined a little since early 2023, while nonfarm payrolls have continued to rise at a solid pace as employers reported their immigrant workers on the establishment surveys (blue).

The coming up-revision of total employment in the household survey should raise the red line and re-establish the typical difference to the blue line.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

The post Census Bureau Massively Revises Up Population Growth: +8 Million in 3 Years, +3.3 Million Last Year, Largely due to Immigration. US Population Surges to 340 Million appeared first on Energy News Beat.